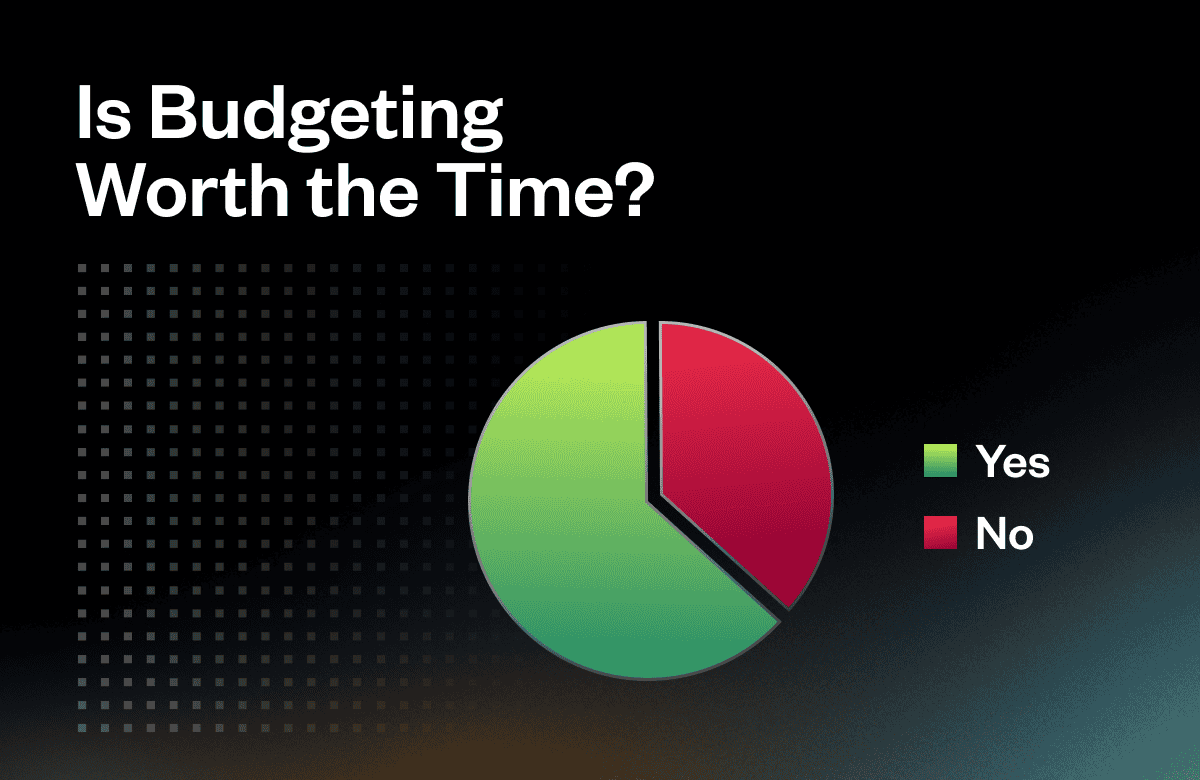

Over a third of finance people don’t think budgeting is worth the time.

That’s a pretty lousy grade for a task every company performs, and it comes from the people who lead the effort.

The data are derived from a LinkedIn survey of 126 people, which is not the gold standard in quantitative research. Yet, the results are directionally correct and consistent with the views of most of the people I interviewed.

It’s also clear that budgeting is not going away, nor should it, but what can we do to improve a process many see as broken?

I asked the most competent people I know from the highest-performing organizations how they approached budgeting. Executives and VCs I spoke with included CEOs and CFOs from Berkshire Hathaway, KKR, Bessemer, P&G, Danaher, Battery, and many others. They do not have all the answers, but they certainly have some good ideas, which are shared below.

Why do we even do budgets? There are two broad objectives of budgeting: resource allocation and performance management.

Resource Allocation

Most folks agree that it makes sense to periodically step back from the business and assess where you want to invest your capital. This process begins with an overall strategy discussion and ends with a hiring plan (for SaaS) and a budget. The company’s competitive position, macroeconomic conditions, and capital constraints all play a role in this process.

Budgets address questions such as:

Will you be investing more in product development or sales next year?

Are you building out the executive team or cutting staff to reach break-even?

Is growth or profit more important?

In this annual resource allocation exercise, many of the executives I chatted with framed the target of the budget to be 50/50. Meaning it was set in a manner to be achieved 50% of the time, so it is the team’s best guess as to next year’s results.

From a resource allocation perspective, a “stretch budget” makes little sense because it is an inherently biased plan and is less likely to be accurate. Making spending decisions based on anything other than your most likely plan will lead to poor choices.

Forecasting

Everyone I spoke with developed forecasts in addition to the budget. Forecasts are updated budgets covering the remainder of the year and are typically updated monthly or quarterly. The budget itself does not change.

If cash is of concern for your company, as it is for most SaaS companies, a 50/50 budget with regularly updated cash forecasts is the optimal planning framework.

Performance Management

Surprisingly, there was less consensus regarding using the budget as a tool to run the business.

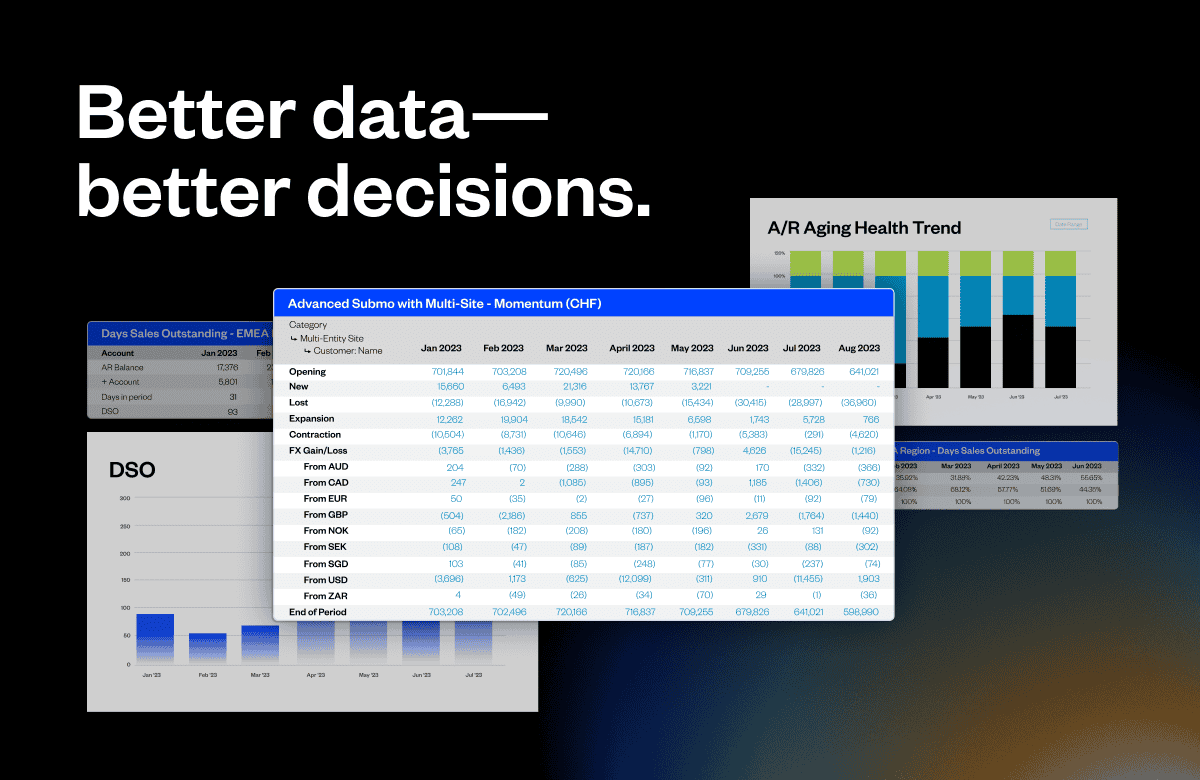

One highly successful CFO took over a finance department that developed a detailed variance analysis only to discover that other management team members and investors found it useless and never looked at it. The owners and operators did care about variances in revenue and EBIT, but detailed line-item variability descriptions provided little insight into the business’s performance.

Budgets can be full of detail, but that does not improve accuracy. One executive referred to detailed line-item budgeting as “precisely inaccurate” and one of the biggest time sinks.

Many executives, myself included, find performance comparisons to last year’s results more instructive for understanding and managing performance. Many people I spoke with used a standard reporting format comparing current results to the budget, forecast, and prior year results. This reporting framework gave them the broadest and most beneficial perspective. It helps managers isolate performance variability from budgeting misses.

Stepping back, it’s a little arrogant to think that constructing a budget and attempting to force the company to hit that budget is the best way to run a company. Businesses do not operate in a vacuum. My notes are littered with quotes about planning from famous presidents and generals, but my favorite is from Mike Tyson, “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” Managing a business is dynamic and iterative, and while it might make sense to align resources with a long-term strategy periodically, it’s naive to place too much importance on that annual plan in light of a dynamic marketplace.

To that point, in one case, the CEO and CFO explicitly told business leaders that they would be fired if they failed to spend money that they should have spent just because it was not in the budget. Conversely, spending money unnecessarily just because it was in the budget would be just as harmful to one’s career. In other words, managers are expected to run a business, not hit a budget. The budget is a tool.

Incentive Compensation

Not everyone ties incentive compensation to the budget. Many argued that linking compensation to the budget drives value-destroying behavior (see above) and is at odds with building a 50/50 budget.

Another benefit of decoupling the budget from incentive compensation is reducing the need for buy-in from deep in the organization. A significant resource drain of budgeting is pushing the process down in the organization to drive employee buy-in. This is much less necessary when it’s not directly tied to compensation.

Instead of tying compensation to the budget, several companies tied comp to performance compared to the prior year, with some adjustments made based on major macro events such as a pandemic or financial crisis.

Scale matters

The utility of a budget is inversely proportional to the size of the company, and smaller firms with little predictability in their top line should spend less time budgeting. If next year’s revenue might realistically be somewhere between $5 million and $10 million, budgets won’t help you manage that business much. Smaller companies absolutely need to forecast and manage cash, but that is a separate and more iterative process.

For smaller businesses, build your expense budget around major areas of significant investment, but don’t spend too much time trying to add detail and precision to an inherently unpredictable revenue forecast. In my experience, revenue forecasts based on simple extrapolated growth rates with minor adjustments are more accurate than detailed “bottom-up” forecasts built with pipeline metrics and quotas.

The Budget and the Board

Most investment documents require the management team to build and deliver an annual budget to the Board, but there is never any detail beyond that.

Without further conversation, the board may be looking for a “stretch budget” while the CEO is building a 50/50, and there will be an unnecessary time-wasting back-and-forth trying to find the middle ground.

Prior to the budgeting process, the CEO should explain her general approach to budgeting and how she will use it. The board should also discuss their expectations (first amongst themselves and then with the management team). The top-down input early in the process should eliminate large disparities, unnecessary negotiations, and wasted time.

Budgets are a Tool

My primary takeaway from all these interviews was the de-emphasis of the budget. Budgets are a helpful part of the necessary annual planning process, but our collective ability to predict the future is weak. Tightly linking the budget to management reporting and incentive compensation elevates the budget above its actual relevance.